Released: July 30, 1954

Released: July 30, 1954Director: Richard Quine; Screenplay: Roy Huggins based on the novels “The Night Watch” by Thomas Walsh and “Rafferty” by William S. Ballinger; Cinematography: Lester White; Music: Arthur Morton; Producer: Jules Schermer; Studio: Columbia Pictures

Cast: Fred MacMurray (Paul Sheridan), Philip Carey (Rick McAllister), Kim Novak (Lona McLane), Dorothy Malone (Ann Stewart), E.G. Marshall (Lieutenant Carl Eckstrom), Allen Nourse (Paddy Dolan), Phil Chambers (Briggs), Alan Dexter (Fine), Robert Stevenson (Billings), Don C. Harvey (Peters), Paul Richards (Harry Wheeler), Ann Morriss (Ellen Burnett)

This one is likely to be looked upon as a stretch in the ranking, as traditionally Richard Quine’s Pushover has been discarded as an inferior imitation of the classic Double Indemnity. In terms of greatness, this one wouldn’t register in a countdown, even one this large in scope. So my own taste and discretion is the main factor for placing it inside the top half of the countdown. Is it derivative of Double Indemnity? Sure it is, but I’m not claiming that it’s at the same level as that masterpiece. But I stand by the contention that this one has been unfairly cast aside precisely because of the Double Indemnity similarity, despite the fact that there is enough variation to keep it fresh. It may not be completely original, but the claustrophobic atmosphere – with similarities to Rear Window (released later in 1954) as well – that Quine creates, and the lead performances of Fred MacMuarray and Kim Novak, I am at a loss as to why Pushover is so easily overlooked.

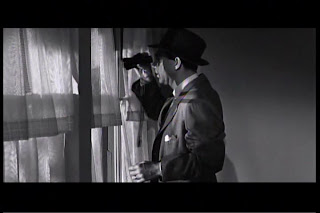

The film opens with a bank robbery gone awry. Things are going smoothly until a security guard tries to play the hero and is gunned down in a gun fight. The robbers escape with $200,000, but their leader Harry Wheeler (Paul Richards) is quickly identified as the mastermind and is pursued by the authorities. Detective Paul Sheridan (Fred MacMurray) is charged with locating the missing money and to do so he decides to try and get close to Wheeler’s girlfriend Lona McLane (Kim Novak). Going undercover, Paul begins wooing Lona in order to extract information about Wheeler’s whereabouts, but in the process the two genuinely begin to fall in love. When Paul finally reveals to Lona that he is a police officer, Lona uses her pull to draw the detective into a dangerous scheme. She proposes the two of them murdering Wheeler when he tries to come back to her, then running off together with the robbery money. At first, Paul rejects the offer, but eventually comes back to Leona and agrees. Paul is then left to figure out a feasible plan that takes into account the significant surveillance operation that he and the police have put together. From a building across a courtyard that looks directly into Lona’s apartment, the police are maintaining 24-hour surveillance. He is juggling things very well, keeping his fellow officers completely clueless, until Wheeler finally shows up. Things do not go as planned, and after complications with the killing of Wheeler, Paul is then forced to go even further to keep his partners from catching onto him.

The close confines of everything are what most come through. The deeper that Paul gets drawn in, the more apparent the claustrophobia becomes. The police are able to see everything that Lona does, can listen to every call coming in and out, which means that any maneuvering that Paul tries to do to further their plot is also potentially there to be observed. This creates some wonderful opportunities for Quine to amp up the tension with very simply situations. Innocuous events like a missed telephone call or a glance down a hallway are enough to create tension that matches high-octane thrillers. The more chances Paul takes, the more suspicious that his colleagues become, and you begin to wonder how long he can string things along before everything falls apart. It is not really constructed like an action movie or conventional thriller, but it is just as intense. Adding to the overall noir atmosphere is the fact that literally everything takes place at night, in the close quarters of an apartment or on the dark streets of L.A. just outside the building.

MacMurray is his always-solid self, a staple noir actor for playing intelligent men who can’t help but get themselves in over their head. The revelation here is Kim Novak in her first starring role. Her Lona is another element that distinguishes Pushover from Double Indemnity. Lona is not an ice-cold villain in the Phyllis Dietrichson mold. She undoubtedly manipulates Paul into the original plan, but she is no puppetmaster directing what he does. Paul takes control of things once the plan is set in motion. The other unique thing about the dynamic of this relationship is that Paul and Lone seem to genuinely care for each other.

This is the second time that a Richard Quine film has appeared in this countdown, and considering that I have only ever seen two movies that he directed, that is quite an accomplishment. On the basis of those two efforts, I look at him as an unsung champion of noir. I’m sure I value this one far higher than most that read this, but like Drive a Crooked Road, I can’t deny how well it works for me.

Pushover is a wide-screen noir as hip as an LA martini. Darkly forlorn like an empty city street at the witching hour. There is also a strong element of voyeurism later explored by Hitchcock in Vertigo.

ReplyDeleteInteresting is Tony’s analogy to “Vertigo”, I always thought it more in line with the voyeurism of “Rear Window” as you mention. Interesting enough both films were released in the same year within a week of each other as I note in my review, which is attached here.

ReplyDeletehttp://twentyfourframes.wordpress.com/2009/08/24/pushover-1954-richard-quine/

Novak looks great and there is some sharp dialogue between her and MacMurray when he “coincidently” meets her outside the movie theater early in the film. Definitely an underrated work Dave and you do a great job here.

Tony - A wonderfully terse description here and one that I agree.

ReplyDeleteJohn - I do see the Rear Window connection more than Vertigo also, but in general it plays with the same kind of issues that Hitchcock loved to toy with. I certainly remember your review, which was outstanding, and I encourage everyone to check it out as well.

Dave, I haven't seen this one or DRIVE A CROOKED ROAD. But they both sound right up my alley. I did want to mention STRANGERS WHEN WE MEET, a later Quine film that I have seen that feels very noirish, too. You might want to take a look at some point.

ReplyDeleteWow, looking forward to each day as you draw closer to #1! Great work, Dave!

Dave, as I stated at Tony and John's sites, I have not yet seen this noir (of all the film genres I have more "holes" with noir than any other, but with you guys forever on the prowl, I have more motivation than I could hope to generate from any other source) I get your point about the derivitive nature of the film unfairly compromising it, as few films could ever be considered in the same league as DOUBLE INDEMNITY. MacMurray and Noval alone would make this a must-see. But your vaunted placement here does speak volumes, and I hope to soon rectify the situation.

ReplyDeleteA bold choice, and a superb essay informing it.

Sorry guys, may aged brain is sliding, I meant Rear Window...

ReplyDeleteJust watched on 40.2 in Sacramento. Truly great film noir. Never have seen Double Indemnity, and look forward to it, but agree, this film deserves much better treatment than its been given.

ReplyDeletegood movie, a very underrated one don't you think?

ReplyDelete