Why simply post a Top 25 at the Wonders in the Dark Best of the 2000s poll, when I can drag it out over an entire week at my own blog before officially submitting my list?! (Ha!) Actually, this is a way for me to direct those that don't normally frequent WitD to stop by and participate in the polling and following the Top 100 that Allan unfolds each day. And also, for my own purposes, to say that what I would like to do next involves the 2000s decade. This isn't a huge undertaking, as the previous two projects were, just something quick that also serves a purpose for finally get up my Top 25 at WitD. As the noir countdown was winding down, I began working on perfecting my Top 25 for the 2000s poll, catching up on films that I had missed and re-watching favorites to perfect placement. So that is where most of my movie-watching has been lately, so why not put it to use?

I know that I posted a Top 20 of the decade at the new year, but that was a pretty quick off-the-cuff effort, and my rankings have changed quite a bit - be it through reshuffling the order or new additions of films that I have seen since making the original rankings. My idea is to actually do a Top 50 here, with daily (or maybe every other day, I don't know) posts that will unveil ten films at a time. These aren't going to contain reviews, but more like thought capsules that express why I'm a fan of each film. I saw this done by Kevin Olsen at his awesome blog Hugo Stiglitz Makes Movies and like Led Zeppelin plundering the catalogs of blues legends, I decided I'd sort of rip the idea off here (LOL). I like the idea of this, allowing me to touch on a number of great films in a short period of time, while also solidifying the list that I will be submitting at WitD. There is still much from the decade that I have not seen, but I still think I can make a pretty intriguing Top 50.

I know I said I was going to take some time off, and from massive projects like the Top 100s, I definitely am. But this one is not going to require quite as much time and work in getting each piece together as the noir countdown. So, if all comes together, I'll start posting these next week in all likelihood.

Tuesday, April 27, 2010

Monday, April 26, 2010

Film Noir Wrap Up

I don’t know how to approach this wrap-up without sounding cheesy and parroting what I said in summation of the annual countdown last November, but all of the same praise still applies. None of this stuff would be any fun for me if I simply wrote the posts, put them up, and then never heard anything back. The fun for me comes in seeing how other people react to a film, discussing placement, analyzing films if necessary, and then learning about other films for me to seek out. All of that took place over the course of this countdown. For those that were along for the entire ride – I don’t want to single folks out for fear of leaving deserving visitors off, but you know who you are - I give major thanks. It has made the entire project rewarding and worthwhile for me. I can’t thank everyone enough.

As I said going into it, the list is going to be far from definitive. I have seen A LOT of film noir, but I also have not seen many films that likely deserved a shot at placement in the countdown. Initially, I thought this might mean that I shouldn’t be undertaking a task of this scope. But I do have to give credit to a lot of the folks who encouraged me to go through with it – I remember Samuel Wilson and Ed Howard in particular essentially saying, “use your own definition of noir and just do the countdown” (paraphrasing of course!). So I did and I am glad that I listened to such advice.

Still, a Top 100 may look impressive, but it really only scratches the surface. The other thing to point out is that I personally learned much throughout the exercise as well. As has been pointed out to me quite clearly, there are a number of films that likely should be on such a list. Some of the omissions are entirely my own decision. A few recognized classics I have never really cared for (Crossfire, The Naked City, This Gun For Hire, Fallen Angel to name a few). There are other films that I have not seen, but probably should have before making a Top 100 (While the City Sleeps, His Kind of Woman, Odds Against Tomorrow, The File on Thelma Jordon, a lot of Brit Noir). And then there are others that I have had difficulty tracking down copies of, badly want to see, but just haven’t had the opportunity yet (City That Never Sleeps, They Won’t Believe Me, Tomorrow Is Another Day). Whether it was money, time, or effort I’ve just never had the chance to watch them. I’ve been told by someone recently that this basically invalidates the entire effort, and if people feel this way, then so be it. I make no claims to be an authority – I’m just a film buff who loves noir and wanted to get started on a countdown. It actually keeps me excited to know that there are still a number of highly-respected noirs out there that I can look forward to.

Others I consciously left off. Trying to define what is and is not film noir is tricky and I probably wasn’t always one hundred percent consistent. For instance, I included a Melville in Le Doulos, but decided not to include Bob le Flambeur. For whatever reason, I’ve always looked toward Bob le Flambeur as more of a straight heist film – similar to how many people interpret Rififi, which I added to the list. I don’t really know how to explain situations like this then to go back to my “Potter Stewart theory” of defining what I think is a film noir. Deciding which films fit into certain labels or categories was light years harder than doing something like a yearly countdown, so rather than getting bogged down in this morass, I felt it was best just to make a decision and stick with it. Once I got going, I tried not to second guess myself. Is a film like Bob le Flambeur a noir? Possibly. But the flip-flopping that could potentially take place in trying to decide whether to include it (and other films for that matter) in the countdown would have brought everything to a standstill. The same goes for Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter. Many people consider this one of the greatest noirs ever made. It certainly has many characteristics of a noir, particularly with the expressionistic lighting. But to me, it has always played more like a gothic story that has the look of a film noir. There are a countless number of films that have some element of noir – Citizen Kane, A Place in the Sun, Johnny Guitar and a number of noirish westerns – so the list could have been extended infinitely.

The one conscious decision I did make was to leave Alfred Hitchcock out of the countdown. It’s nothing against Hitch – as anybody who follows my blog knows, he is probably my all-time favorite director. It was another situation where deciding what qualifies and what doesn’t gets very dicey. Many people consider Notorious a film noir, but it has never seemed one to me. What about Vertigo? Shadow of a Doubt? Strangers on a Train? The Wrong Man? Cases can be made for each of them, although Strangers on a Train and The Wrong Man are probably the only ones that I would feel completely confident including in such a countdown.

Basically, this is a longwinded explanation of how genre-based countdowns are inevitably going to be tricky. I haven’t seen everything, and of what I have seen, my definition of which ones qualify as film noir is bound to differ from someone else’s. So with that in mind, I would love for everyone to post their own personal lists of their favorite/best noirs. Top 10s, 20s, 100s, whatever... I would just love to see other lists from everyone else!

DIRECTORS

I also thought it would be interesting to see the directors that had multiple appearances in the countdown. This list features a lot of the usual suspects, but some other less-celebrated directors also are highlighted:

-Fritz Lang - 5 films (#20-Scarlet Street; #22-The Big Heat; #66-Clash by Night; #97-The Blue Gardenia; #100-The Woman in the Window)

-Jules Dassin - 4 films (#9-Rififi; #23-Brute Force; #29-Night and the City; #84-Thieves’ Highway)

-Henry Hathaway - 4 films (#32-Kiss of Death; #72-The Dark Corner; #82-Niagara; #95-Call Northside 777)

-Robert Siodmak - 4 films (#4-Criss Cross; #5-The Killers; #19-Cry of the City; #98-Phantom Lady)

-Norman Foster - 3 films (#53-Woman on the Run; #58-Kiss the Blood Off My Hands; #85-Journey Into Fear)

-Samuel Fuller - 3 films (#44-Underworld U.S.A.; #55-Pickup on South Street; #96-House of Bamboo)

-John Huston - 3 films (#10-The Asphalt Jungle; #15-The Maltese Falcon; #73-Key Largo)

-Anthony Mann - 3 films (#37-T-Men; #39-Raw Deal; #68-Side Street)

-Nicholas Ray - 3 films (#6-In a Lonely Place; #69-They Live By Night; #78-On Dangerous Ground)

-Orson Welles - 3 films (#18-Touch of Evil; #51-The Lady from Shanghai; #92-The Stranger)

-Billy Wilder - 3 films (#7-Double Indemnity; #8-Sunset Boulevard; #42-Ace in the Hole)

-Andre de Toth - 2 films (#13-Pitfall; #40-Crime Wave)

-Byron Haskin - 2 films (#31-Too Late for Tears; #65-I Walk Alone)

-Phil Karlson - 2 films (#47-99 River Street; #59-Kansas City Confidential)

-Joseph H. Lewis - 2 films (#27-The Big Combo; #48-Gun Crazy)

-Anatole Litvak - 2 films (#75-Out of the Fog; #81-Sorry, Wrong Number)

-Joseph L. Mankiewicz - 2 films (#43-House of Strangers; #61-Somewhere in the Night)

-Rudolph Maté - 2 films (#50-D.O.A.; #77-Union Station)

-Jean Negulesco - 2 films (#46-Nobody Lives Forever; #81-Road House)

-Otto Preminger - 2 films (#30-Laura; #35-Where the Sidewalk Ends)

-Richard Quine - 2 films (#49-Pushover; #56-Drive a Crooked Road)

-Raoul Walsh - 2 films (#36-White Heat; #74-High Sierra)

-Robert Wise - 2 films (#24-The Set-Up; #71-Born to Kill)

Although Fritz Lang put the most films in the countdown, what was solidified in my own mind after completing the list is that Robert Siodmak and Jules Dassin are, in my opinion, the two greatest directors of film noir. In terms of personal taste, I already knew this to be the case with Siodmak. Re-watching many of the classics reminded how great Dassin was as well. It’s also nice to see directors like Henry Hatahway and Norman Foster, who aren’t normally talked about as much, place multiple films in the list.

So chat away about anything regarding the Top 100 and also please submit your own personal lists!

Where to next? I have no clue… at least a little bit of a break from extensive lists or countdowns.

Saturday, April 24, 2010

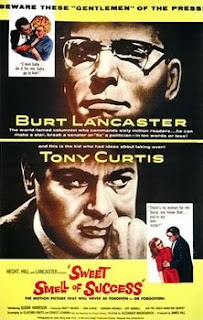

#1: Sweet Smell of Success (Alexander Mackendrick, 1957)

Released: June 27, 1957

Released: June 27, 1957Director: Alexander Mackendrick; Screenplay: Clifford Odets, Ernest Lehman, and Alexander Mackendrick (uncredited) based on a novelette by Lehman; Cinematography: James Wong Howe; Studio: United Artists; Producer: James Hill; Music: Elmer Bernstein

Cast: Burt Lancaster (J.J. Hunsecker), Tony Curtis (Sidney Falco), Susan Harrison (Susan Hunsecker), Martin Milner (Steve Dallas), Sam Levene (Frank D’Angelo), Chico Hamilton (Chico Hamilton), Barbara Nichols (Rita), Emile Meyer (Lt. Harry Kello), Jeff Donnell (Sally)

- “Mr. Falco, let it be said at once, is a man of forty faces, not one - none too pretty and all deceptive.”

Not much suspense left in reaching #1 I suppose, as once the shock of Out of the Past coming in as the runner-up subsided, it certainly became obvious what would take the top spot. That comes with the territory, though, as everyone had a general idea as to what the final ten films would be, so it was just a matter of marking them off the list as things played out.

But, I did at least manage to elicit some shock, which I suppose could create a backlash toward crowning Alexander Mackendrick’s Sweet Smell of Success as #1 in the film noir countdown. The general consensus seems to be that Out of the Past is the more logical choice, and as you can tell from my intro yesterday, I grappled with the decision myself. In terms of “greatness” or historical significance, it’s a no contest, Out of the Past would take the title with very little opposition. My own taste, as of right now, though, leans toward Sweet Smell of Success. Watching it again, I was just too drawn into the darkened atmosphere that James Wong Howe so smoothly creates. I became too intoxicated by Elmer Bernstein’s jazzy score. And the two lead performances remain just as blistering on the ninth or tenth viewing as the first. Ask me in two weeks how I would rank my favorite noirs and the top two might flip, but for now I simply have to go with Sweet Smell of Success.

I have been trying to come up with a greater one-two punch of lead performances that would top Tony Curtis and Burt Lancaster and have drawn a complete blank. To my knowledge, such a film simply doesn’t exist. They both give powerhouse turns. Sidney and J.J. are equally cruel, but the actors manage to elicit diametrically opposite sympathies from an audience. J.J. is the nominal villain; the man that everyone wants to see chopped down to size. Sidney is just as devious, but Curtis plays him in such a way that it’s hard not to grudgingly root for him.

As I discuss in the review below, this is a case of all the elements coming together, with all of them playing a significant role in the final product. Lancaster, Curtis, Mackendrick, Wong Howe, Bernstein, Odets, Lehman – without the contributions of each individual person, things would not be the same. They come together to create a dark, cynical portrait of late-night Manhattan that somehow manages to be both repugnant and irresistible. This is another film that I have never grown tired of and can watch at any time.

Oh, and once again, I point everyone to the script. I might throw the term around loosely, but it unquestionably qualifies as a masterpiece.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

If I wanted to get really cute with this review, I would simply post a link to the Odets and Lehman penned screenplay, copy and paste a picture of both Tony Curtis and Burt Lancaster in their roles from the film, and end things at that. That would be more than sufficient in summing up why I consider this film to be not just the best of 1957, but among the finest that I have ever seen. In reality, my review of the film is just going to be expounding on these key strengths, while also singing the praises of the stunning nighttime photography of New York City. I almost never refer to a film as perfect, but I have to admit that when it comes to Sweet Smell of Success, there is nothing that I would argue needs to be changed.

The background on how the stars aligned to bring all of the principals in the film together is interesting. The script, cast, and production team were put together in stages, with each new addition to the team adding something to the final product. The story is based on a magazine story by Ernest Lehman that originally was published in 1950, basing the story on his own experiences working in the New York public relations industry. When the film rights to the story were acquired, Lehman quickly began to work to direct it himself. United Artists balked at the idea, not wanting a novice director causing problems. It was then that the producers turned to a director who had not worked in the United States in over twenty years – Alexander Mackendrick. Mackendrick, although born in the U.S., had moved back to Scotland at an early age and had been working in the film industry in Britain since the 1930s. He had made many successful films as a director at Ealing Studios, but with the sale of company, Mackendrick began casting his eyes toward Hollywood. Courted by the Hecht-Hill-Lancaster production company, which had the rights to Lehman’s script, Mackendrick agreed to come back to the States and take over director duties.

Mackendrick and Lehman began working together to tailor the script to the new director’s liking, but soon hit a snag when Lehman fell sick and was no longer able to continue. Into his place stepped Clifford Odets, who began reworking the script even further. I have personally never seen it pinpointed as to exactly what Odets was changing with the script, but it apparently was extensive, as the editing continued even after shooting began. Apparently, it was not changes to the actual storyline, but more of a refining role to improve individual scenes and dialogue. Whatever it was, it worked, as the script is superb, and all three men who had a hand in working on it deserve praise.

It is also Hollywood lore that Universal Studios, which owned Tony Curtis’ contract, was vehemently opposed to him playing the role of Sidney Falco. Curtis, on the other hand, lobbied hard to land the role and fortunately won out – if Curtis ever did better work than in this film, I haven’t seen it. I'll go a step further and say that there are few performances I've seen in _any_ film that top Curtis as Sidney Falco. Orson Welles was supposedly considered for the role of J.J. Hunsecker, a thinly veiled depiction of Walter Winchell, but United Artists pushed for the box office appeal of leading man Burt Lancaster. This is another choice that has been shown to have been correct, as Lancaster showed his versatility. Normally in films noir, Lancaster would play characters that were at heart well-intentioned men, but for whatever reason would be swept up in uncontrollable circumstances. As Hunsecker, he is playing a man with virtually no redeeming qualities.

The screenplay and its story are as biting as you’ll ever encounter. It follows a night in the life of press agent Sidney Falco (Tony Curtis), a PR man who can hustle with the best of them. As with every other press agent in the city, his number one goal in life is to get his clients mentioned in the newspaper gossip column of the powerful J.J. Hunsecker (Burt Lancaster). Although promised lines in the column, Falco is continually rebuffed by Hunsecker because he has been unable to deliver on a promise made to J.J. Falco had agreed to break up the romance between Hunsecker’s sister Susan (Susan Harrison) and rising jazz guitarist Steve Dallas (Martin Milner). Until that objective is achieved, Sidney is being shut out from the Hunsecker column.

Over the course of the night, the audience has a firsthand view of Sidney’s bouncing from nightspot to nightspot, meeting with clients, currying favor with journalists and doing his best to schmooze with important people. He also continues doing his damndest to pull Susan and Dallas apart from each other. Throughout the night he also meets with J.J. as the columnist holds court at his usual restaurant table. It is here that we see the power of J.J. Husecker as he has politicians and celebrities coming to him for favors, nearly groveling just to get an audience with him.

I’ve already sung the praises of the screenplay, and I won’t do my usual cut-and-paste of favorite lines (although I will post a link to the actual screenplay: http://www.awesomefilm.com/script/sweetsmell.html). As I said at the beginning of this piece, aside from being my all-time favorite screenplay, there is more than just the excellent writing to admire here. The two lead performances are absolute masterworks, particularly Tony Curtis. Sidney Falco is downright sleazy, with no limitations on what he will do to curry favorable press. In an ironic way, he wears this characteristic as a badge of honor – after all, in his eyes he is just doing his job. As one of his clients tells him, “It’s in a publicity man’s nature to be a liar.” But Sidney goes beyond simply lying. He is outright manipulative, and uses anyone he can to help him out of a jam – his secretary, his sometime girlfriend, his uncle. The amazing thing is that Curtis is so charismatic in the role that you can’t help but at least grudgingly like Sidney. Was this intended by the writers? I don’t know, but if it wasn’t then it is further proof that Tony Curtis as Sidney Falco is the ultimate conman!

All of this action takes place in exactly the setting that one would expect such shady characters to be operating in. I know that I am always harping on the atmosphere of great films, but it’s impossible not to admire the dark New York City streets and nightclubs captured brilliantly by Mackendrick and cinematographer James Wong Howe. They craft the perfect mood for the biting script and subject matter. The streets are dark, with smoke rising from every opening, swirling around the press hounds and P.R. men bustling about and lending a sinister undertone to nearly everyone encountered in the film. This movie isn’t dark in the same sense as other noirs, where there is a doomed feeling attached to every action. It is dark in a very literal sense – everything takes place at night and even when things are happening indoors, they are taking place in dimly lit bars or clubs. It might be reading too much into this fact, but it could very easily be interpreted that these bloodsucking press men are the modern equivalent of vampires who cannot see the light of day. Combine this with the jazz soundtrack of Elmer Bernstein and things are as I (correctly or not) picture New York City to have been at this time.

The story is acerbic and at times can be utterly cruel. Yet it’s always so much fun to watch. Maybe it says something about me and the many other fans of the film that find such biting humor to be so funny and entertaining… I’m not really sure. What I do know is that if we’re talking just pure enjoyment, there are times when I’m tempted to proclaim Sweet Smell of Success as my #1 film of any year.

Labels:

Curtis,

Film Noir,

Lancaster,

Mackendrick,

Noir Countdown

Friday, April 23, 2010

#2: Out of the Past (Jacques Tourneur, 1947)

Released: November 13, 1947 (U.S.A.)

Released: November 13, 1947 (U.S.A.)Director: Jacques Tourneur; Screenplay: Daniel Mainwaring (as Geoffrey Homes), based on his novel Build My Gallows High; Cinematography: Nicholas Musuraca; Studio: RKO; Executive Producer: Robert Sparks; Producer: Warren Duff

Cast: Robert Mitchum (Jeff Bailey), Kirk Douglas (Whit Sterling), Jane Greer (Kathy Moffat), Paul Valentine (Joe Stefanos), Rhonda Fleming (Meta Carson), Steve Brodie (Jack Fisher), Virginia Huston (Ann), Dickie Moore (The Kid), Ken Niles (Eels)

Even I am shocked at this placement. This had to be the odds on favorite to take the top spot in the countdown and it came very close to doing so. If I were asked for a recommendation of a single film to show someone as an example of film noir, it would be Jacques Tourneur’s Out of the Past. If I had another day to think about it, this one might be swapped into the #1 position. It is such a toss-up for me on how to separate my top two that I almost need to go with the classic copout of 1a and 1b. But, I’ll refrain from taking the easy way out, and instead make the toughest call that I have had to make in any of the lists made at this blog.

It truly is a testament to the greatness of this film that I am scrambling to rationalize why it did not finish in the _top spot_. Think about what praise this is for a movie to be ranked #2 in a field as storied as film noir. Out of the Past is so good that it is jarring not to see it at numero uno.

The combination of director Jacques Tourneur and cinematographer Nick Musuraca is one of the great duos in the history of Hollywood. They worked together on a number of masterpieces – I Walked With a Zombie was chosen as my top film of 1943 and Cat People is routinely cited as one of the greatest horror pictures ever made – but even those classics pale in comparison to Out of the Past. The two masters were responsible for preparing the template that allowed Robert Mitchum to deliver his most iconic performance and for Jane Greer and Kirk Douglas to turn in towering performances as well.

If you can’t tell, I almost feel guilty not putting this at #1. No amount of analysis or examination can do justice to how great this film is and how well it holds up to countless viewings. Movies like Out of the Past are why I am obsessed with cinema.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

There are certain films that I find extremely hard to write about or critically examine. These are films that I have some kind of deep emotional connection to – favorites from my childhood, movies that I saw at a key point in my life, or films that were absolutely essential to my development as a fan of cinema. So, I’m usually hesitant to try and overanalyze why I love them so much. This is one of those films. Out of the Past was the first film noir that I ever watched and it was nothing short of earth-shattering for me. I’ve been a noir junkie ever since, getting my hands on every noir I can, but all the time failing to find a single one that matches this 1947 classic. So, with that warning, I’ll go ahead and try to analyze it anyway. If I’m gushing in the review, it’s because this is one of my all-time favorite movies.

Out of the Past is on a shortlist of noirs that I would categorize as quintessential. If someone were to come to me and ask for a definition the style, I would direct them to this and Double Indemnity. If neither of those caught their attention, then it would probably be safe to assume that noir is not for them. The reason for such a bold proclamation? Out of the Past contains all of the archetypal elements of great noir. Adapted from a pulp novel. Private eye main character. Ruthless femme fatale. Shady gangster businessman. A story told in large measure through flashbacks and narration. And an unrelenting sense of destiny at every turn.

Oh, and Robert Mitchum. If Humphrey Bogart crafted the mold for the cool, tough guy noir P.I., then Mitchum perfected it in this film.

The story opens with the Mitchum character of Jeff Bailey working at a gas station in a small rural town. Little is known about Bailey’s history and this secretive nature arouses a bit of suspicion in the small town of Bridgeport, as evidenced by the negative reaction of his girlfriend Ann’s (Virginia Huston) parents. His attempt at distancing himself from his past is destroyed when gangster and ex-acquaintance Joe Stefanos (Paul Valentine) tracks Jeff down at the gas station. Joe tells Jeff that his ex-employer, wealthy gambler Whit Sterling (Kirk Douglas), is looking for him and sets up a meeting.

At this point Jeff is forced to reveal the truth to Ann concerning his life before Bridgeport. While driving to the meeting with Whit, Jeff recounts the tale to Ann, warning her that “Some of it’s gonna hurt you.” He says that his real name is Jeff Markham and that he used to be a New York private eye. A few years earlier, Whit hired Jeff to track down his runaway girlfriend and $40,000 that disappeared with her. The search takes Jeff to Mexico, where he finds the stunningly beautiful Kathie Moffat (Jane Greer). Rather than bringing her back to Whit, Jeff falls in love with her. They sneak away back to the States and begin to live life as a normal couple. But Whit has not forgotten his former love interest, the $40,000 dollars, or the private eye that he hired and who then vanished. Whit enlists Jeff’s old partner, Jack Fisher (Steve Brodie), to track him, which he does after randomly spotting him at a local racetrack. When the partner finds the couple and tries to extort them, Kathie insists that he won’t be revealing anything to Whit. She ensures this by gunning Jack down, then speeding away from the scene and leaving Jeff to bury the body. With Kathie again in the wind, Jeff then moves to Bridgeport and attempts to finally be rid of his former life. This pipedream is forever wrecked when Joe catches up with him at the gas station. Realizing that he has no choice but to confront his past, Jeff agrees to the meet with Whit and plunges himself back into the shady world he tried so desperately to abandon.

While at the meeting with Whit, Jeff discovers that Kathie has reunited with the gangster. Rather than being angry with him, Whit enlists Jeff for another job. But sensing that he might be getting caught up in a frame, Jeff has to navigate a path that keeps him safe from his employer, the law, and a variety of characters he comes in contact with along the way. Will this job set Jeff free from his past? Can he pay his debt to Whit and then resume his life with Ann in Bridgeport? Whose side is Kathie truly on? I’ll let you discover the answers to these questions yourself, as it’s a wild ride for the entire 97 minutes, chock full of plotting, double crossing and tense face-offs. For those that have already seen the film, I’m sure you’ll agree that the answers are always shifting and keep the viewer wondering.

The story has been characterized by some as convoluted, and it is, but don’t let anyone fool you into believing that it’s incomprehensible. The script is expertly crafted by Daniel Mainwaring, adapted from his own novel Build My Gallows High (both written under the pseudonym Geoffrey Homes). For as many twists and turns that take place throughout the story, the screenplay is surprisingly tight, with none of the conspicuous plot holes that have plagued some otherwise great noirs. And the dialog… oh my, the dialog. The lines come shooting out of characters’ mouths like daggers. Some of my favorite lines in all of cinema come from this film and from Mitchum in particular. The examples are numerous and outstanding:

“Kathie: Oh, Jeff, I don't want to die!

Jeff: Neither do I, baby, but if I have to I'm gonna die last.”

-----------

“Ann: She can't be all bad. No one is.

Jeff: Well, she comes the closest.”

-----------

“Kathie: Oh Jeff, you ought to have killed me for what I did a moment ago.

Jeff: [dryly] There's time.”

I could go on for pages. I’ll forever maintain that Jeff’s response in the first example is my favorite line of all time. This dialog is razor sharp and the epitome of cool. The brilliance of these lines is in large measure due to Mainwaring, as just reading them is terrific. But a lot of credit must also go to Mitchum. As Jeff Bailey, he is the personification of the detached anti-hero and makes these words come alive. These witty expressions would be nowhere near as powerful if they weren’t being delivered by the droopy-eyed Mitchum, adorned in an overcoat and stylish hat and with a cigarette hanging between his lips. The way that Jeff Bailey navigates this underhanded world and interacts with such shady individuals, the role calls for someone to be able to add the necessary cynicism to the character. Mitchum is precisely the man. It’s no coincidence that despite being his first top-billing, this is the role for which Mitchum is best remembered. He is that good.

I could go on for pages. I’ll forever maintain that Jeff’s response in the first example is my favorite line of all time. This dialog is razor sharp and the epitome of cool. The brilliance of these lines is in large measure due to Mainwaring, as just reading them is terrific. But a lot of credit must also go to Mitchum. As Jeff Bailey, he is the personification of the detached anti-hero and makes these words come alive. These witty expressions would be nowhere near as powerful if they weren’t being delivered by the droopy-eyed Mitchum, adorned in an overcoat and stylish hat and with a cigarette hanging between his lips. The way that Jeff Bailey navigates this underhanded world and interacts with such shady individuals, the role calls for someone to be able to add the necessary cynicism to the character. Mitchum is precisely the man. It’s no coincidence that despite being his first top-billing, this is the role for which Mitchum is best remembered. He is that good.As previously mentioned, the major themes that are found throughout all film noir are on display here, but this film outdoes nearly all of them in key areas. The sense of danger hanging over a likeable, yet flawed character has never been done better. It is impossible to ignore the fact that Jeff _willingly_ walks back into a world and situation that he knows could very well be his downfall. The audience knows this too, and it is distressing to see him continue down a path that everyone involved – audience and characters, Jeff in particular – knows is not likely to end well. To say that there is a sense of doom hanging over the events would be an understatement. And yet, in the end, there is redemption of sorts. The closing scene between Ann and Jeff’s deaf gas station attendant is poignant and reveals that Jeff may have been in control of his destiny all along.

The direction of Jacques Tourneur also deserves recognition. Darkness and shadows are the staples of any director working in film noir. However, few were ever able to utilize them as effectively as Tourneur, as he juxtaposed them with beautiful pastoral settings. Whenever Jeff is in Bridgeport, the scenes are wide open and bright, setting Jeff and Ann in front of a backdrop of rolling mountains, streams, and the country. But as soon as Jeff comes into contact with anyone from his past – be it Kathy, Whit or Joe – the scenes become dark and gloomy. Faces are obscured by shadows and movement becomes sinister as silhouettes creep across the screen. These are interesting contrasts and emphasize the wildly different worlds that Jeff is attempting to jump between.

After spending so much time referring to this as the quintessential film noir, I have to admit that such praise is almost doing the movie a disservice. Pigeonholing it as the best of a specific genre is too restricting for a film this good. Out of the Past is not just one of the best films noir, it is one of the greatest films of all time, period.

Thursday, April 22, 2010

#3: Kiss Me Deadly (Robert Aldrich, 1955)

Released: May 18, 1955

Released: May 18, 1955Director: Robert Aldrich; Screenplay: A.I. Bezzerides from the novel of the same name by Mickey Spillane; Cinematography: Ernest Laszlo; Studio: United Artists; Producer: Robert Aldrich

Cast: Ralph Meeker (Mike Hammer), Albert Dekker (Dr. G.E. Soberin), Maxine Cooper (Velda), Cloris Leachman (Christina Bailey), Gaby Rodgers (Lilly Carver/Gabrielle), Nick Dennis (Nick), Paul Stewart (Carl Evello), Juano Hernandez (Eddie Yeager), Wesley Addy (Lt. Pat Murphy), Marian Carr (Friday), Jack Lambert (Sugar Smallhouse), Jack Elam (Charlie Max), Leigh Snowden (Cheesecake), Percy Helton (Doc Kennedy)

As is the case with most cult movies, it seems that viewers either love Robert Aldrich’s Kiss Me Deadly or find it too over-the-top to take seriously. Where I fall on that spectrum is obvious – I think Kiss Me Deadly is one of the best movies I’ve ever seen. It is a film that stands alone, meaning I can think of few others to really compare it to. Certainly it shares stylistic traits with other great noirs, and the general storyline contains a mystery that will feel familiar. But the apocalyptic nature gives it a flavor all its own.

My thoughts after watching it again are similar to this review from the annual countdown. The expert pacing used by Aldrich once again stands out to me. Never has the paranoia and obsession of a lead character been so skillfully thrust directly onto an audience. Watching the film, you feel exactly like Mike Hammer does – intrigued, feeling perpetually on the verge of solving the mystery, yet never fleshing everything out until it is too late. By the time he (and we as the audience) figures out what is being sought, it is too late to realize that it is not something that he should be so eager to find.

This is a “desert island film” for me, which is ironic because the ending supports the idea of a couple of folks ending up alone on some sort of remote island!

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Kiss Me Deadly remains overwhelming in the number of different ways that it can be enjoyed. It is a movie that contains enough action and entertainment to be enjoyed as your usual noir thriller, yet is also meaningful enough to be analyzed for its cultural significance. The first time that I ever watched it, I came away as a fan of the film, looking it as a slightly above average private eye noir. Comparing it to other similarly structured films, I found it to be good, but wasn’t nearly as enthusiastic about it as I am now. I put it aside and carried on with other films before coming back to it a few years later. When I returned to it, now more familiar with the context in which the film was made and its impact on the course of cinematic history, my appreciation skyrocketed. I quickly realized that I wasn’t simply watching a hardened variation of a Raymond Chandler story. In fact, as I’ve come to view it, this story actually plays as something of a swansong to that era of stories and characters.

Opening with one of the most classic of opening sequences, a woman in a trench coat is seen running down the middle of a highway. Standing in front of an oncoming car in order to force someone to stop, she causes private detective Mike Hammer (Ralph Meeker) to run his convertible off the road. While giving her a ride to the nearest gas station, Hammer quickly realizes that his new passenger has escaped from a mental hospital and is wanted by authorities. She (Cloris Leachman) convinces him not to turn her in, hauntingly imploring him to “Remember me” if things go wrong. They of course do, as the car is overtaken by assailants and the girl is killed. Hammer manages to survive, waking up in the hospital after spending three days in a coma.

Hammer emerges from the hospital curious as to the circumstances that led to the girl’s death. His interest is further piqued when both law enforcement and underworld personalities begin probing him for information about what the girl may have revealed to him. Rather than focusing on the usual divorce PI work that he uses to make his living, Hammer and his secretary/sometime-girlfriend Velda (Maxine Cooper) begin following any leads on the mysterious girl. The more tantalizing the potential lead, the more obsessed Hammer becomes with unraveling this mystery that no one appears to know the answer to. Following this trail brings Hammer into contact with a wide range of characters, from the girl’s supposed former roommate Lilly Carter (Gaby Rodgers), to underworld heavies like Carl Evollo (Paul Stewart) and his henchman Sugar Smallhouse (Jack Lambert) and Charlie Max (Jack Elam). For all of the leads that Hammer appears to continually be uncovering, he somehow never seems to get closer to the truth – until it’s too late for him to decide whether he really wants to discover that truth. By the time that Hammer finds a mysterious black box, which appears to harbor a substance or force of unspeakable power and intensity, events seem to have spiraled out of anyone’s control.

The fact that Kiss Me Deadly was made toward the end of the “classic” film noir era is unsurprising, as it plays like a rejection of so many of the central tenets that characterized the genre. Whereas Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe may have been poking their noses into places they didn’t belong, in the end they proved themselves to be valuable as they busted crime or saved others from harm. Mike Hammer sees himself in a similar light, acting as if he is the only person who can truly resolve the mystery of what happened to Christina Bailey and what she was trying to hide. No matter who tells him to leave it alone – the police, gangsters, his friend and close confidant Velda – Mike thinks that he can find justice for any wrongs that have been committed. With every tidbit of information he receives, Hammer becomes more intrigued, always appearing to be on the verge of grasping what it is that he is chasing, but never quite unmasking the truth. What he fails to realize is that in his pursuit, he is causing even more damage in the process, and is setting off a chain of events that will lead to catastrophic consequences. When Mike finally does realize that this is what is happening, it’s far too late for him to reverse course. The mysterious black box has already been discovered, there are already other people who covet whatever it is that the box represents, and there is no way for the box to be discarded or forgotten.

The brilliance of director Robert Aldrich in this film is that he shoots the film to make the audience feel the exact same thing. Until becoming fully aware of what is happening (which took me more than a single viewing), the viewer is going to approach the mystery of the story in the same way as Mike Hammer. Each new bit of evidence is seen as bringing us one step closer to discovering why such sinister men were hell-bent on silencing Christina. And with each new clue, we too feel like we might be able to guess what is going on. It never happens. The audience realizes the stakes involved at the same time that Hammer does, and as I said, at that point there’s no turning back. The conclusion is still stunning today, even when it becomes obvious what is going to happen. Right up until the explosive finish, I kept thinking "He's really not going to end the movie like this is... is he?". It works the whole way, which also shows how strong the script from veteran A.I. Bezzerides is. To have something this outlandish and over-the-top come across so well is a testament to strong writing.

Robert Aldrich would go on to much more financially-successful endeavors and would direct films that were much more popular with the general public (The Dirty Dozen, Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?), but this B-movie masterpiece is undoubtedly his artistic zenith. This film is stylish to the max, as Aldrich and cinematographer Ernest Laszlo experiment with camera angles and different shot structures. It is little surprise that this film would go on to be a major influence on the French New Wave in the coming years. Aldrich and Laszlo combine to wonderfully capture the gritty feeling of Los Angeles, making every setting and character have a seedy quality. There is also a realization is how adept Aldrich is at handling violence. Filming at a time when explicit displays of violence was not acceptable, Aldrich had to get very creative in order to get across the viciousness of the sequences of events that Hammer is a part of. Simply, yet highly creative shot compositions are able to make otherwise benign sequences become absolutely chilling. The greatest example comes very early in the film when Christina and Mike are captured by the unnamed assailants. The men are torturing Christina, trying to find out what she revealed to Mike. As they are working her over, all the camera focuses on are her feet. We see her feet squirming as she struggles to avoid the pain. When a bloodcurdling scream is heard and the feet give one final anguished jerk, it is clear that the young girl has been killed. Without seeing one drop of blood or a single second of the interrogation, Aldrich still manages to startle the audience.

It is film noir meets Cold War paranoia, which likely sounds like the recipe for a horribly cheesy movie – and in most cases it would turn out this way. Fortunately, Aldrich never allows the film to slip into such territory. Some still argue that the film feels dated, and even if that point is conceded, it does nothing to detract from its greatness. If it’s dated, it’s dated in the same way that The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band is dated – meaning that something similar isn’t likely to be made any time soon, but that it’s still better than almost anything else likely to be produced. Even so, I would argue strongly that the film most definitely is not dated. While the makeup of world politics may have changed in the fifty years since its release, the tendency for people and groups to deal in absolutes has not. There are still segments of society who refuse to see things in any way but there own or to follow any course of action but the one that they are certain is right. As is the case with Mike Hammer, this oftentimes can serve to make things worse. This is still a relevant film, with themes that can be applied to circumstances other than the Cold War.

Wednesday, April 21, 2010

#4: Criss Cross (Robert Siodmak, 1949)

Released: January 12, 1949

Released: January 12, 1949Director: Robert Siodmak; Screenplay: Daniel Fuchs based on the novel by Don Tracy; Cinematography: Franz Planer; Studio: Universal International Pictures; Producer: Michael Kraike; Music: Miklós Rózsa

Cast: Burt Lancaster (Steve Thompson), Yvonne De Carlo (Anne Dundee), Dan Duryea (Slim Dundee), Stephen McNally (Detective Lt. Pete Ramirez), Tom Pedi (Vincent), Percy Helton (Frank), Alan Napier (Finchley), Griff Barnett (Pop), Meg Randall (Helen), Richard Long (Slade Thompson), Joan Miller (the Lush), Edna Holland (Mrs. Thompson), John Doucette (Walt), Marc Krah (Mort), Esy Morales (Rhumba Band Leader)

That closing shot continues to stick with me. The screen cap that closes this write-up really says it all. It not only reinforces what a visual stylist that Robert Siodmak could be, but it sums up what film noir is all about. When I think of noir and the doomed relationships that populate its greatest films, that image epitomizes it.

If there was a dark horse for the number one slot in the countdown, this would have been it. I couldn’t quite bring myself to move it to that level, over unmitigated cinematic classics that occupy the top three spots, but I was certainly tempted. I consider it to be the crowning achievement of Siodmak’s career, even if it is often overshadowed by earlier efforts like The Killers and The Spiral Staircase. What stuck with me most in this latest viewing was how unsettled the feelings of Steve are throughout the story. He continually refers to how something “was in the cards” and how fate seems to have dealt him a rotten hand, yet at other moments he tells people that he will “make his own decisions.” It’s as if he knows that his own wrong choices are leading him down this path, yet he wants to believe that it is destiny.

Film noir at its finest…

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

There has already been a Siodmak-Lancaster collaboration included in this countdown, as Lancaster’s screen debut The Killers was selected at #5 in the series. My love for that film hopefully came through in my review, making clear that I consider it to be among the best noirs that I have ever seen. Going against conventional wisdom, I actually think that in this follow-up effort the two combined to make an even better film. While The Killers may contain more iconic scenes and is routinely cited as being influential on later crime films, Criss Cross remains in my mind as Siodmak’s best film.

To be certain, there are obvious similarities between the two films. A cursory examination of the plot would lead one to believe that they are closely related – the nice guy turning to the underworld (who happens to be played by Lancaster in both instances), a doomed romance, a love triangle, double cross after a heist, use of flashbacks. Each of these elements is seen in both movies. Linking the two would be something of a stretch, however, because these elements are present in countless films noir. The fact that such similar stories and themes are played out in a vast number of movies, and yet The Killers and Criss Cross manage to distinguish themselves from any related films, is testament to the brilliant hand of Siodmak.

In Criss Cross, the focus is on Steve Thompson (Burt Lancaster), who returns home to Los Angeles after some months away. He had fled the city in the face of a deteriorating marriage to Anne (Yvonne De Carlo). After returning to his working class neighborhood, reuniting with old friends and visiting old haunts, Steve cannot shake memories of his romance with his stunning ex-wife. While hanging around the bar that the couple frequented together, one night Steve spots Anne on the dance floor. There is obviously still chemistry between the two and they begin to move toward getting back together. However, Steve’s best friend Lt. Pete Ramirez feels Anne is a terrible influence on his pal and manages to drive Anne away from him. In an act equal parts spite and defiance, Anne runs off and marries flashy gangster Slim Dundee (Dan Duryea).

Even the marriage cannot keep the two apart. They continue their romance secretively, realizing that if Slim were to catch them there would be hell to pay. Despite their caution, Slim does manage to catch the two of them together in his house. Thinking fast, Steve manages to concoct a reason for his being alone with Anne. He tells Slim that he came to Anne in order for the opportunity to pitch a job to him. Steve says that he has planned a heist of the armored car company that he works for, using himself as the inside man needed to pull off the job. After the job is agreed to, the necessary scheming transpires, with Steve and Anne secretly planning to double-cross Slim and his gang and escape with the loot.

I will stop short of revealing how everything plays out from this point forward, but there are certain sequences that transpire that I can praise without revealing exactly how the film concludes (in case there are those that have not yet seen it). The heist sequence is fabulous, as Siodmak and cinematographer Franz Planer make use of smoke to convey the complete confusion and disorientation of the heist. Amidst this chaos, it is hard for both characters and the audience to make out who is who. Such confusion is how I would imagine such a tense situation to be and that is precisely the feeling that Siodmak and Planer are able to communicate to the viewer. The other obvious aspect of the heist is that it is somewhat brutal for its time, with guards and burglars alike being gunned down in similar brutal fashion.

Lancaster is his usual excellent self as Steve Thompson. I’m not sure whether I prefer his performance here or as the Swede in The Killers, but I do know that as Steve he creates an incredibly friendly character. He is pulled into the criminality because he is trying to save himself and Anne from harm, whereas the Swede willingly turned to the rackets. While I’ll admit to not having seen the bulk of Yvonne De Carlo’s work, this is as good as I have seen her. The Anne character is intriguing because of her ambiguity. Is she good or bad? Honest or conniving? Even among femme fatales that are horribly callous, there is at least a sense of what their true intentions are. Not so with Anne, who kept me guessing as to whether her loyalty was truly with Steve or if she was conniving with Slim.

The Siodmak-Planer duo must be commended for the portrayal of the city of Los Angeles. That opening flyover shot is great, as the camera swoops over and then descends into Los Angeles at night. The depiction of L.A., and specifically the Bunker Hill section of Steve’s home, has a very realistic quality, showing a working class area that is becoming more and more middle-class in the postwar boom. L.A. is a common setting for noir, but Criss Cross has a feel that makes it distinct from others set in the City of Angels. The underbelly of the city obviously exists, as embodied by Slim Dundee, but for whatever reason there is not quite the same darkness permeating every character as is seen in films such as Double Indemnity.

This lack of omnipresent darkness, however, does nothing to dampen the gloomy conclusion. Rather than type out a long interpretation, I’ll finish in the same way that the film does, with the memorable closing shot.

Tuesday, April 20, 2010

#5: The Killers (Robert Siodmak, 1946)

Released: August 28, 1946

Released: August 28, 1946Director: Robert Siodmak; Screenplay: Anthony Veiller, Richard Brooks (uncredited), John Huston (uncredited) based on the short story by Ernest Hemingway; Cinematography: Elwood Bredell; Music: Miklós Rózsa; Producer: Mark Hellinger; Studio: Universal Pictures

Cast: Burt Lancaster (Ole “Swede” Andersen), Ava Gardner (Kitty Collins), Edmond O’Brien (Jim Reardon), Albert Dekker (Big Jim Colfax), Sam Levene (Lt. Sam Lubinsky), Vince Barnett (Charleston), Virginia Christine (Lily Harmon Lubinsky), Charles McGraw (Al), William Conrad (Max), Charles D. Brown (Packy Robinson), Jack Lambert (Dum-Dum Clarke), Donald McBride (R.S. Kenyon)

After rereading my entry in the annual countdown for 1946, I feel very satisfied and proud of the entry. There isn’t a whole lot that I feel like I can add without getting repetitive. Instead, my thoughts once again turn to the fact that Robert Siodmak is, in my opinion, the most underrated director of the 1940s. He seems to routinely be pigeonholed – The Spiral Staircase is a great horror movie, The Killers is a great noir – but is never talked about in the same breath with the likes of Welles, Ford, Hawks, and others. Certainly the bulk of his work in this period took place in noir, but his greatest movies transcend genre classification. The Killers, Criss Cross, The Spiral Staircase are flat-out great movies. No qualifier needed.

But… since this is a countdown devoted exclusively to film noir, I will go out on a limb and make another bold statement. Robert Siodmak, in my opinion, can make the greatest case to being the finest director to ever work in the genre/style/whatever you want to call it. His best work is of that high of quality.

So I re-post my original review here and once again marvel at how that opening diner scene never ceases to give me goosebumps each time I watch it.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

All it took in deciding to place The Killers this high in the countdown was re-watching that classic opening scene another time. The aforementioned opening scene and the killing that follows are the only parts of the film based on Ernest Hemingway’s original short story. The biting dialogue and wisecracks of the two hitmen, sent to kill an ex-boxer named Swede for an unknown reason, is possibly the best part of film. The killers, Al (Charles McGraw) and Max (William Conrad), banter with the owner and make clear that they are hired guns simply doing a job. I always smirk when Al asks “What do you do here nights?” and Max mockingly answers “They all come here and eat the big dinner.” The killers then proceed to fulfill their contract, bumping off Swede (Burt Lancaster) without incident.

Following these first 20 minutes, the story is entirely new. Screenwriter Anthony Veiller (apparently with uncredited help from John Huston and Richard Brooks), crafts a story to fill in the background of events that led Swede Andersen to willingly lay in bed and allow gunmen to kill him. The idea of taking a short story like this, which makes perfectly clear that our main character is murdered, and then creating a suspenseful mystery by filling in the details through flashbacks, is very interesting. It doesn’t matter that we know that the Swede will ultimately be murdered. As you follow insurance investigator Jim Reardon (Edmond O’Brien) researching the life of the Swede, it becomes intriguing to discover how the Swede fell from a first-rate boxing attraction to someone who seemed to welcome his own death. In this sense, the structure of the film is very much like that of Citizen Kane, where we know where things will end but are absorbed in finding out how the story will reach that point.

The plot centers on the Swede after he realizes that his fighting career is over. No longer able to make his living in the ring, Andersen finds that the most lucrative career choice is to enter the numbers racket and work his way up in the underworld. In the process, he becomes enamored with Kitty Collins (Ava Gardner), the girlfriend of powerful hoodlum Big Jim Colfax (Albert Dekker). After Swede takes a rap for Kitty and goes to prison to keep her out of trouble, he emerges from jail and is drawn into a robbery scheme put together by Colfax. From there, double-crosses and backstabbing emerge as various members turn on each other. Kitty runs out on Swede and Swede in turn retreats to the small town life he was leading before his murder.

Director Robert Siodmak is not only a celebrated noir director, but one of my all-time favorite directors of any genre. Not knowing the specifics of the production, it is hard for me to pinpoint precisely who is most responsible for the look of this film, so I’ll go ahead and give co-credit to both Siodmak and cinematographer Elwood Bredell. The majority of the film is shot in interiors that are extremely dark. Just witness the image of the Swede lying in bed, surrounded by shadows, listening as his murders scale the stairs to his room. Such dark images are contrasted by the few scenes taking place outside, such as when Reardon visits Lt. Sam Lubinsky (Sam Levene) and they have lemonade on his roof. These scenes are much brighter, creating an interesting distinction between the two settings. These brighter images reinforce the dark underworld that the Swede has entered, and also offer a glimpse of the life that he could have led if he had followed in the footsteps of friends like Lubinsky.

I know people whose opinions I respect that feel scenes like the opening moments in the diner and other times in this film come across as cheesy. I cannot possibly disagree more, but I’ve realized that changing personal tastes is a completely futile exercise. The Killers will always have a special place for me, as it was the film that convinced me that Burt Lancaster was a truly brilliant actor and that Robert Siodmak is a man who deserves much more praise than he currently receives. It is still amazing for me to think that this was Lancaster’s debut film. Still, I am honest enough to admit that this is not a perfect film, as the sudden change in attitude of the Swede as he moves from pugilist to numbers man comes across as rather abrupt and not well-developed. But such a shortcoming is more than made up for by Siodmak’s deft direction and the way that Hemingway’s entertaining short story is expanded in reverse. It is among a handful of my favorite noirs.

Monday, April 19, 2010

#6: In a Lonely Place (Nicholas Ray, 1950)

Released: May 17, 1950

Released: May 17, 1950Director: Nicholas Ray; Screenplay: Edmund H. North and Andrew Solt based on the novel by Dorothy B. Hughes; Cinematography: Burnett Guffey; Music: George Antheil; Producer: Robert Lord; Studio: Columbia Pictures

Cast: Humphrey Bogart (Dixon Steele), Gloria Grahame (Laurel Gray), Frank Lovejoy (Det. Sgt. Brub Nicolai), Carl Benton Reid (Capt. Lochner), Art Smith (Mel Lippman), Martha Stewart (Mildred Atkinson), Jeff Donnell (Sylvia Nicolai), Robert Warwick (Charlie Waterman), Morris Ankrum (Lloyd Barnes), William Ching (Ted Barton), Steven Geray (Paul, the Headwaiter), Hadda Brooks (Singer)

- “I was born when she kissed me… I died when she left me… I lived a few weeks while she loved me.”

The further I dig into the work of Nicholas Ray, the deeper my appreciation of his craftsmanship grows. His visual style is well-documented, and one need only watch something like his aerial shots in They Live By Night to immediately grasp the fact that he had an eye for space and camera movement on par with anyone else in Hollywood. Such technical skills certainly impress me, but what comes through most in his work is the passion. Everything the man directed seems to ooze intensity, whether it is a passionate relationship, a boiling anger, or an unbridled obsession. Nearly all of his films feature characters that openly display this type of raw emotion, which Ray would expertly balance with moments of compassion. This resulted in characters that felt not like players in a film, but fully-developed, lifelike people – sometimes likable, sometimes reprehensible; sometimes gentle, sometimes violent; sometimes caring, sometimes heartless. Like you or me, like real people. For all of the talk of certain types of films or filmmakers creating “ambiguous characters,” Ray’s films remind me that _all_ people are morally ambiguous at some point; some just have a penchant for leaning more toward the dark than the light, or vice-versa.

This comes through loud and clear in what I consider the finest film Ray ever made, 1950’s In a Lonely Place. Big-screen idol Humphrey Bogart gives the darkest performance of his career as Dixon “Dix” Steele, a Hollywood screenwriter who hasn’t seen success in years. He previously enjoyed success, but then reached the point that he could not churn out mundane scripts at the rate that studio executives demanded – he contends that he has to find a story that he truly believes in. So rather than filling his time with work, Dix’s life begins a continual cycle of alcohol and violent eruptions of his legendary temper. One night at popular Hollywood hangout Paul’s, Dix’s agent (Art Smith) tells him he has a novel that a studio is asking to be adapted for the screen. They want Dix to write the screenplay, but Dix shows very little interest in doing any work. Since he refused to read the actual novel, he decides to bring hatcheck girl Martha Stewart (Mildred Atkinson), who recently read it, to tell him the story. After a couple minutes, Dix quickly comes to the conclusion that it is another disposable story and sends Martha on her way. When he awakes the next morning and is greeted at his front door by longtime friend Brub Nicolai (Frank Lovejoy), a police officer, he is told that Martha was murdered shortly after leaving his house.

Dix naturally becomes the lead suspect in the case, but an unlikely witness provides him with enough of an alibi to convince the police to release him pending further investigation. Struggling actress Laurel Gray (Gloria Grahame) recently moved into Dix’s apartment complex and testifies that she was up late that night and saw Martha leave the apartment alone. After his release, Dix grows closer to Laurel and a torrid affair begins. The love interest spurs Dix’s creative muse, as he sets off on his most productive writing sessions in years. This results in his producing a brilliant script and plans for marriage with Laurel. But the murder investigation hounds them at every turn, and the more that Laurel learns about Dix’s past – including multiple arrests for assault and other violence – the more she questions the relationship. Is it possible that he really did murder Martha? Even though she doesn’t think so, the question threatens to plague any future plans they make.

The movie runs barely over an hour and a half, which I point out because the economy of it all is astounding. Over the 94-minute running time, Ray guides the viewer through a maze of emotions and interpretations. When the mysterious murder is announced, it is actually pretty obvious to the audience that Dix is not the culprit. We saw Dix give Martha the cab money, send her on her way, and then retire to a hibernation-like sleep. So unless you think Nick Ray is going to pull off one majorly unbelievable swerve, then it is obvious that Dixon did not commit the murder. Or is it? Writers Edmund North and Andrew Solt expertly pace the revelation of details concerning Dix’s violent past, while Ray perfectly times the inclusion of brutal outbursts to ensure that the suspicion festers. The greatest example of this, and arguably the best scene in the entire film, takes place when Dix visits Detective Brub Nicolai and his wife for dinner. While discussing the case, Dix argues that as a longtime writer of murder mysteries, he could solve the crime easier than could the police. Dix sets up a recreation of the fateful car ride, instructing Brub and his wife Sylvia (Jeff Donnell) to act it out. As Dix describes the horrible actions, he becomes completely caught up in the storytelling, in the process getting Brub overwhelmed as well. As Dix gets more amped up in describing the strangulation, Brub loses his own self-control and begins squeezing his wife’s neck to the point that she screams for help. The sadism that can be seen in Dix’s eyes as he narrates the murder makes the question seem even more up in the air.

Still, like Laurel in the film, the viewer is likely to remain at least somewhat confident that Dix did not commit the murder. The greatness of the film derives from the fact that solving the mystery becomes unimportant. The question eventually becomes not did he do it, but does it even matter? Even more terrifying for Laurel is the realization that he is certainly capable of doing something that wicked. That awareness, even without confirmation one way or the other on the actual murder, is enough to keep her from committing. Grahame’s performance as the alluring Laurel is, in my opinion, the finest of her career. The conditions under which she worked on this film are also legendary, as her marriage to director Nick Ray was already starting to fall apart when filming began. It is amazing to consider how their deteriorating relationship mirrored the doomed affair of Dix and Laurel. As Dix began to enter the greatest creative outburst of his career, his relationship with Laurel crumbles under the pressure. So too did the marriage of Ray and Grahame, who separated during filming and would divorce two years later.

Also fascinating is how In a Lonely Place provides commentary on the effect that the Hollywood culture can have on those around it. This is a different interpretation from what is done in another 1950 classic, Sunset Boulevard. In that film, Wilder examines how Hollywood treats past stars, the people that are no longer profitable to those in power. In a Lonely Place looks at what can happen to entertainment personalities who are right in the middle of it all, trying to make a living and get by in that same world. It seems to show that even those who are finding work, who are still productive, can find it just as isolating as those that have been cast aside.

Little more needs to be said about Bogart’s performance – others have said it more articulately than I can. I still maintain that while Rick Blaine is certainly his most iconic role, his performance as Dix Steele is his best. Only Bogart’s turn as Fred C. Dobbs even approaches the same level of darkness seen in Dix. Watching him fight inner demons for the entire film is both unnerving and spellbinding. This is not necessarily a pleasant film to watch, but the craftsmanship on display from the Ray, the principle actors, and the great Burnett Guffey make it so powerful that you can’t help but return to it.

Sunday, April 18, 2010

#7: Double Indemnity (Billy Wilder, 1944)

Released: September 6, 1944 (U.S.)

Released: September 6, 1944 (U.S.)Director: Billy Wilder; Screenplay: Billy Wilder and Raymond Chandler based on the novel by James M. Cain; Cinematography: John F. Seitz; Studio: Paramount Pictures; Producers: Buddy G. DeSylva and Joseph Sistrom

Cast: Fred MacMurray (Walter Neff), Barbara Stanwyck (Phyllis Dietrichson), Edward G. Robinson (Barton Keyes), Tom Powers (Mr. Dietrichson), Jean Heather (Lola Dietrichson), Byron Barr (Nino Zachetti), Porter Hall (Mr. Jackson), Fortunio Bonanova (Sam Garlopis), John Philliber (Joe Peters), Richard Gaines (Edward S. Norton, Jr.)

As is the case with other films that I have already written extensively about (or at least what I consider to be extensive, meaning in terms of blog posts), I don’t feel it necessary to write completely new takes on such movies. I easily chose Double Indemnity as my #1 for 1944 and it is a no-brainer to place it comfortably within the Top 10 for the noir countdown. Still, I think that there needs to be something additional added onto these pieces, at the very least to show that I’m not piggybacking on past work at this point. And so I made a point to re-watch each of the movies in the Top 10, to bring some new thoughts to each entry.

Watching Double Indemnity for the umpteenth time, there is one thing that drew all of my attention: the work of John Seitz. Since seeing Double Indemnity for the first time, I have never been able to look at venetian blinds the same again. I’m not kidding – anytime I see shadows or light slithering through the slits in such blinds I am reminded of this movie. I have praised Seitz’s work throughout the countdown, particularly in regard to his work in yesterday’s Billy Wilder entry Sunset Boulevard, and all of it is more than deserved. His photography is distinctive. It doesn’t have the grittiness of the work of John Alton. Instead, Seitz’s work is what I like to call stylishly dark. It has smoothness to it, yet never sacrifices the darkness. My realization of just how great Seitz was remains one of the biggest eye-openers of this whole series. I knew he was great, but I didn't fully appreciated the consistent excellence of his work until recently.

My other thoughts on the film are well captured in the piece below. I’ll just add that I go back and forth concerning my favorite Billy Wilder noir. Sometimes it is Double Indemnity, sometimes it is Sunset Boulevard. The fact that they ended up back-to-back in the countdown was not planned, and in fact they only ended up in those positions very late in the process. For now, Double Indemnity wears the crown, but it’s a tough call between such classics.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- "I killed him for money and for a woman. I didn't get the money and I didn't get the woman. Pretty, isn't it?"

Just looking at the notables involved in every facet of this legendary film is enough to make a classic movie fan or noir buff salivate. The cast is superb, combining diverse on-screen personalities that result in maximum tension. With Barbara Stanwyck having already perfected the role of a manipulative, ambitious vixen in earlier pre-Code films, she is the ideal fit as the calculating Phyllis Dietrichson. Fred MacMurray, who until this point had played mostly wholesome, friendly characters, is cast against type as the man who is drawn into Mrs. Dietrichson’s machinations. It is a brilliant casting decision, as although Walter Neff takes an active role in the planning, the persona of MacMurray manages to convey the sneaking suspicion that the insurance agent is in over his head and is being maneuvered. Edward G. Robinson plays Barton Keyes, a claims adjuster who is hell-bent on uncovering any fraudulent claims submitted to the Pacific All-Risk Insurance Co. While not as ruthless as the gangster characters that made Robinson a star, Keyes is every bit as resolute and determined toward his job. The script is based on a novel by one of the godfathers of pulp fiction, James M. Cain. It is adapted for the screen in part by another of the titans of the hardboiled genre, Raymond Chandler, who infuses his trademark snappy dialogue with the dark themes of Cain’s story. The soundtrack is handled by the celebrated Miklós Rózsa. The photography of John Seitz is appropriately dark and shadowy. And the entire affair is overseen by arguably the most versatile director of his era, Billy Wilder.

On paper, it is a can’t-miss experience. On-screen, it manages to be the equal of such impressive credentials.

It is the story of insurance salesman Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray), who finds himself in the middle of a murderous love triangle after doing something as simple as attempting to renew an automobile insurance policy. While on a call to renew of the policy of Mr. Dietrichson, Neff meets his gorgeous wife Phyllis and immediate chemistry is developed between the two. The sexual tension at this first meeting is palpable. As the two begin an affair, Phyllis sheepishly proposes the idea of purchasing life insurance for her husband, then later progresses to planning to kill him in order to collect on the policy. While he at first resists such an evil idea, Walter eventually comes on board, but decides that if they are to go through with it they are going to go for the gusto. If they can make Mr. Dietrichson’s death appear to be an accident, they will collect twice as much through the double indemnity clause.

When Mr. Dietrichon is found dead on railroad tracks, apparently having fallen off the back of a slow-moving train, police are quick to conclude his death the result of an accident. Unfortunately for the plotting couple, Barton Keyes (Edward G. Robinson) and Pacific All-Risk are not as easily convinced. Keyes senses something strange and quickly begins to suspect that Mrs. Dietrichson likely plotted with another man to kill her husband. The relationship between Phyllis and Walter is strained as they try to maintain secrecy and keep Keyes from the truth. Meanwhile, as relations between the couple begin to deteriorate, Walter comes to suspect Phyllis of plotting more than just the murder of her husband.

It may not be my favorite film noir, but Double Indemnity remains one that I would put forth as the quintessential expression of the genre. As I have said previously on this blog, couple this one with Tourneur’s Out of the Past and even a complete neophyte will have a perfect introduction to the elements that have become noir staples. The flashbacks, the shadows, the dark lighting, the femme fatale, the unforgiving determinism – all of these components are on display here. But with Chandler involved in the screenplay and Wilder involved in both the screenplay and direction, there is the unmistakable quality of everything being a bit tongue-in-cheek. This is a story dealing with deadly serious issues, and yet nobody in this film – with the possible exception of the never-tiring Keyes – seems to be taking themselves seriously until it is far too late.

This feeling is due in large part to the sarcastic banter between characters. It is biting, cynical, and at times can feel a bit awkward. Lines like Neff telling Phyllis, “Suppose you get down off your motorcycle and give me a ticket” or “They say all native Californians come from Iowa” at first left me scratching my head wondering where in the heck they came from. I may be in the minority, but I truly do feel like some of the dialogue can be unwieldy. But it does fit with the sarcastic nature of the proceedings for most of the film – at least through the planning stages of the murder – as if there is a joke behind everything.

It is also amazing how tense this film at times can be, when considering that from the opening scenes the audience basically knows the conclusion. Early on we see a wounded Walter Neff stumbling into the insurance office and declaring into Keyes’ Dictaphone that his plan did not work out. Within the opening minutes, the plot that he and Phyllis hatched is outlined and he confesses to committing murder, declaring that he now plans to reveal all to his friend and coworker. Even with all of these details, there are moments in the film that are incredibly suspenseful. Just witness the scene when Keyes unexpectedly barges into Neff’s apartment to discuss the Dietrichson case. Unaware of the visitor, Phyllis pays a visit at the same time. Realizing the potential problem, Neff works to keep the two out of each other’s sight. Because of the opening of the film, we know that Keyes is not going to see Phyllis, and yet there is great tension as Walter tries everything to usher Keyes to an exit. Praise must go directly to Billy Wilder for this, as the direction of scenes such as this reinforces how masterful he could be. He is able to take something as simple as a woman hiding behind an open door and make it thrilling.

The other aspect that I did not initially realize, but that on subsequent viewings came to understand, is the fact that this is a rare example of a film that does not have a single likable character. Phyllis is as devious a character as has ever been committed to celluloid. Although it at times seems as if Walter is being manipulated by Phyllis, it’s impossible to overlook the fact that Walter is a willing participant and contributes significantly to the planning of the murder. Even Keyes, the incorruptible claims adjuster, can be irritating. After all, who likes overbearing insurance employees who will do anything to see to it that no money is ever paid out? The only character I ever remotely felt for was Lola (Jean Heather), Mr. Dietrichson’s daughter, but she is primarily on the periphery. It is this dearth of heroes or likable personalities that makes Double Indemnity such a grim film. No matter how much sarcasm or snappy dialogue is rattled off throughout, it is never enough to overcome the fact that these are unpleasant people all the way around.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)