Released: September 12, 1969

Released: September 12, 1969a.k.a.: L'armée des ombres

Director: Jean-Pierre Melville; Screenplay: Jean-Pierre Melville based on the novel by Joseph Kessel; Cinematography: Pierre Lhomme and Walter Wottitz; Studios: Les Films Corona and Fono Roma; Producer: Jacques Dorfmann

Cast: Lino Ventura (Philippe Gerbier), Paul Meurisse (Luc Jardie), Jean-Pierre Cassel (Jean Françoise Jardie), Simone Signoret (Mathilde), Claude Mann (Claude Ullmann/“Le Masque”), Paul Crauchet (Felix Lepercq), Christian Barbier (Guillame Vermersch/“Le Bison”), Serge Reggiani (The Hairdresser)

Jean-Pierre Melville is the only director who could have made Army of Shadows and achieved such spectacular results. There certainly are other directors that have excelled in making “war films” and could have outdone any action sequences that Melville created. There are definitely other directors, both French and around the world, who have successfully explored the struggles of common French citizens in their efforts to resist the Nazi occupation. But in Melville, there was a man who could not only adapt compelling source material for the screen, but also draw upon his own unique experiences in the Resistance movement. Even more importantly, Melville represented a director who quite naturally created characters that went well beyond the clichéd heroes common to many films dealing with World War II. Utilizing his knack for creating the brooding, conflicted people that are used so perfectly in his crime dramas, Melville transplanted these same characters into the setting of 1940s France and allows the audience to appreciate the decisions that these seemingly ordinary men were forced to grapple with.

This is what stands out to me most about Army of Shadows and why I make the bold statement at the beginning of this piece. Knowing Melville’s track record, it seems obvious to me that he was the perfect fit to make the travails of characters like Gerbier, Luc and Mathilde come alive and feel harrowing to everyone watching. In the 1960s, prior to beginning work on Army of Shadows, Melville made three highly-acclaimed crime dramas that presented heroes that were far from perfect. In Le Doulos, Le deuxième soufflé, and Le Samourai, the lead characters are ones that are difficult to classify. These men may be criminals, but they all show redeeming qualities that reveal dualities to their personalities. Nothing is ever completely as they seem with any of them, whether it be Jef Costello or Maurice Faugel.

So it is in Army of Shadows, which feels very much like a noir-meets-war film. Absolutely nothing is black and white. Even when the answers to problems confronted by the various characters appear obvious, the actual execution or implementation of the answer is never simple. This gray area is what makes the drama so riveting. Rather than displaying French heroes performing herculean feats and slaughtering any Nazi in their path, Melville highlights the haunting decisions that must be made by those leading the Resistance. Even though men like Gerbier have dedicated their lives to freeing France and defeating the Nazis, the trepidation with which they make life-and-death decisions for themselves and others feels sincere.

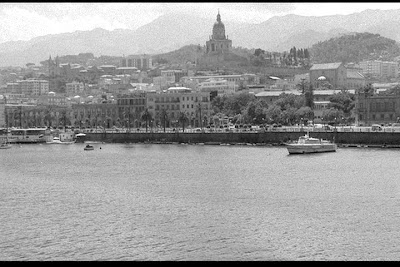

The movie focuses on the efforts of engineer turned Resistance fighter Philippe Gerbier (Lino Ventura), who at the start of the film is being transported to a Nazi internment camp. While being transferred from this camp, Gerbier sees an opening and makes a daring escape. Managing to dodge the gunfire that ensues, he works his way back to Marseille and reenters the Resistance network that he heads in that city. The film then fleshes out the extent of the secretive organizations operating throughout France, as the various contacts that Gerbier works with are revealed. We meet Felix (Paul Crauchet), his second-in-command in Marseille, and the always-effective Mathilde (Simone Signoret), who as a woman appears to be completely above suspicion by the authorities in Paris. There are also more mysterious figures that are known only by codenames like Le Bison (Christian Barbier) and Le Masque (Claude Mann). It eventually emerges that they all answer to a boss in Paris, but only a select few are aware of his true identity (which will not be revealed here!).

The story is told very matter-of-factly, making it the antithesis of any romantic visions of the French Resistance movement or WWII in general. At times, the movie is downright brutal, and will make a viewer squirm and hesitate in the same way that the characters on the screen do. The scene in which Gerbier and his underlings uncover a turncoat and drive him to a safe house in order to execute him makes me uncomfortable in a way that few other scenes I have ever viewed are capable of. They drive the man, who in actuality looks like a boy barely out of his teens, to the house and realize that the neighbors are home. This rules out the original plan of shooting him and disposing of him quickly. The men then begin going over the possible methods of execution, trying to come upon the one least likely to alert the neighbors. All of these machinations take place while the soon-to-be victim looks on, terrified by the fact that he is witness to the planning of his own execution. Plus, the more discussion that takes place, the more time that is allowed for the enormity of the situation to sink in upon Gerbier, Felix, Le Bison and Le Masque. When they finally settle on strangling him, the assassins themselves are so horrified by the prospect that they argue over who is actually going to carry it out. Eventually the man is strangled with a dishtowel and although there is little gore or blood, it is among the most disturbing scenes I have ever seen in film. It is impossible not to sympathize with these men who are trying to act as detached partisan leaders, but can never completely shed their ordinary civilian personas.

Melville couples such psychologically troubling scenes with sequences that are reminiscent of the action sequences he perfected in his gangster films. Gerbier’s escape from the Nazis is the equal of a Hollywood action blockbuster. So too is the distressing scene in which his would-be Nazi executors instruct Gerbier and other captives to start running down a dark hallway in hopes of outrunning the machine guns that they have set up. They tell the men that anyone who can successfully run the gamut will be spared. There are other exciting scenes that are more familiar in similar war films such as Philippe being secretly spirited away to London by a British submarine or his parachuting back into France in order to reenter the country undetected.

Lino Ventura as Gerbier is spot on. As a bespectacled, middle-aged engineer, he is completely believable. He lends credence to the idea that most of the people involved in the Resistance were ordinary citizens thrust into extraordinary situations. When he grapples with important decisions that must be made, the trepidation displayed feels not only understandable but fitting. Jean-Pierre Cassel as Françoise Jardie and Simone Signoret as Mathilde are excellent as well, but it is Ventura who stands out from all of them.

How this movie was released to a middling reception in France and was never officially released in the United States until 2006 is mystifying to me. From the opening iconic shot of Nazi storm troopers marching through the Champs-Elysées until the devastating finale (which, again, will not be revealed here, but let me take the time to reiterate how amazing I feel the finish is), there is hardly a misstep in the entire film. Melville may have directed “better” films, depending on how you want to define that subjective term, but he never made a movie more moving than Army of Shadows.

Rating: 10/10

Other Contenders for 1969: In looking everything over, I realized that 1969 was a very good year, even if there is at least one major film that I couldn't get a copy of to watch for this countdown. The one key film that I have not seen is Costa Gavras' Z, which is one that I'm guessing would be right up my alley. On the bright side, it looks like Criterion is releasing the film in late October, so while that does nothing for this countdown it will be nice to finally get to see it.

As for those that I have seen, there are two favorites in this runner-up category. The first is the counterculture road story Easy Rider, directed by Dennis Hopper. I know that it turns a lot of people off, but I genuinely enjoy it -- the craziness, the great use of pop music, the snapshot of a certain era and subculture. The other is George Roy Hill's Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, which is my favorite Paul Newman-Robert Redford collaboration and among my favorite westerns as well. The other movie that I would acknowledge, although I don't place it in the same category as the previous two, is Sydney Pollack's They Shoot Horses, Don't They?.

For a second straight year I also have to point out that I go against the conventional pick of the top film of this year, as Sam Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch is one that I have never cared for. I can think of two Peckinpah westerns that I find to be vastly superior to The Wild Bunch and have always been surprised to see this one lauded so much more than other efforts of his that I think are much better. Just a personal opinion, and the influence that The Wild Bunch has had on westerns and film in general is undeniable.