Released: October 3, 1958 (Poland)

Released: October 3, 1958 (Poland)a.k.a.: Popiół i diament

Director: Andrzej Wajda; Screenplay: Jerzy Andrzejewski and Andrzej Wajda based on the novel by Jerzy Andrzejewski; Cinematography: Jerry Wojcik; Studio: Zespól Filmowy “Kadr”

Cast: Zbigniew Cybulski (Maciek), Adam Pawlikowski (Andrzej), Waclaw Zastrzeynski (Szczuka), Ewa Krzyzanowska (Krystyna), Bogumil Kobiela (Drewnowski), Jan Clecierski (The Porter), Artur Mlodnicki (Kotowicz)

When thinking about what it must have been like in Europe on May 8, 1945, the day that the German Army officially surrendered to the Allies, one would think that it would be nothing but endless parties and champagne. Looking back now, sixty-plus years removed from it, it’s easy to view everything as if on a timeline, where once World War II officially ended then those affected by it simply picked up the pieces and moved on to the next chapter of the 20th century. This is obviously a ridiculously naïve analysis, but it at times can be hard to understand how such turmoil remained to be experienced in nations that had been ravaged by war for nearly a decade. With Ashes and Diamonds, director Andrzej Wajda attempts to relate the precarious situation that existed in Poland after the fall of the Nazi occupiers. In an incredibly artistic fashion, he manages to show that while the end of the war may have meant the end of some hardships, it most certainly did not mean an immediate return to peace.

The story focuses primarily on a young Polish resistance fighter, Maciek (Zbigniew Cybulski), and the hit team that he is a part of in its assignment to kill a Communist Party leader who is returning to the country. Along with his longtime partner Andrzej (Adam Pawlikowski) and Drewnowski (Bogumil Kobiela), a secretary to the mayor who is feeding them information, the group lays in ambush at a church hoping to catch the motorcade by surprise. When a jeep approaches, Maciek and Andrzej spring into action, machine-gunning the car and dispatching both the driver and passenger. Believing their assignment to be complete, the group quickly leaves the area and goes into the city where they can report their work to be done.

When Szczuka (Waclaw Zastrzeynski), the Communist leader who was the target of the hit team, pulls up in a jeep a few minutes later, it becomes obvious that the wrong men were assassinated. Those passing by the church recognize the two men as cement factory workers, one of whom had returned from a Nazi prison camp just weeks earlier. Recognizing that the bullets were intended for him, Szczuka uses the incident as an example to those witnessing the carnage, proclaiming that it is necessary to take risks like these in order to further the communist cause.

Soon after returning to the city, Maciek is inexplicably face to face with Szczuka, the man he believed he had just killed. When Andrzej reports to his superiors that their mission actually failed, he receives orders that the job be properly carried out that night. Maciek decides that he will finish the job and by sweet-talking a fellow native of Warsaw working at the front desk of a hotel is able to take a room next door to Szczuka’s. Things begin to grow complicated when he meets Krystyna (Ewa Krzyzanowska), a blond bartender working at the hotel. He almost immediately falls in love with her. After the two have a rendezvous in his hotel room, Maciek begins to question the cause that he has devoted himself to. Recognizing that the uprisings, murders, and constantly being on the move have deprived him of ever being able to enjoy pleasures like the love of a girl like Krystyna, he begins to wonder whether he can continue a life on the run. When he takes these concerns to Andrzej, he is all but accused of becoming a deserter. The question then becomes, what Maciek will choose – a “normal” life with Krystyna or carrying out the contract assigned to him and the loyalty demanded by the anti-communist resistance?

In terms of the story, Wajda does a masterful job of depicting the complexity of Polish society in this final day of World War II and outlining the different factions that would jockey for control of its direction in the post-war era. The most impressive thing that is accomplished is how Wajda’s was able to make almost every character serve as a microcosm of a group involved in the struggle. Maciek and Andrzej are the prototypical examples of those in Poland who were staunch resistance fighters, risking their lives in opposition of the Nazis. They continue their fight against the new power, the Soviets, because they feel like they fought not just to rid the country of the Germans but for complete Polish freedom. In the now-ruling Soviets, they feel that their freedom is still being threatened. But there are differences between even Maciek and Andrzej. Adrezej follows orders from resistance higher-ups with a soldierly devotion, whereas Maciek comes across as much more of a free spirit. While this is never completely spelled out in the film, Maciek came across to me as someone who may have originally believed in the justness of his actions but is eventually involved in the fighting because it has become routine. When he sees that his actions have taken the lives of ordinary Poles – the very people he is ostensibly struggling to protect – things are no longer as cut and dry for him.

The moral ambiguity of the film arises when Maciek and Andzej are contrasted with those that they are opposing, in particular Szczuka. Szczuka represents those in Polish society who have wholeheartedly embraced the new Soviet regime that seizes power after the Nazi defeat. Rather than being depicted as an evil communist or traitor to his country, it becomes apparent that Szczuka too considers himself to be a patriot. He also resisted the Nazis and fought to drive them from Poland. His acceptance of the Soviets seems to arise out of a genuine belief that they will better his nation and its citizens. Is he wrong in this belief? Nothing in the film explicitly shows this to be the case. While a viewer may identify with the charismatic Maciek and assume him to be promoting a just cause, Wajda is never so heavy handed as to force the audience to blindly accept this. Szczuka is never shown to be the direct cause of any of the country’s troubles. Thus, Maciek’s questioning his actions becomes completely understandable. It seems only natural for him to wonder if the murder of one man is worth the collateral damage of killing innocent Polish citizens.

Other lesser characters represent equally interesting segments of society. Drewnowski is a man who works as an assistant to the communist mayor, while at the same time providing information to the resistance movement. He appears to represent those in Poland who admire the resistance fighters and long for absolute freedom, while at the same time covering themselves by at least giving the appearance of loyalty to the Soviets. With Krystyna, Wajda shows the Poles who are simply swept into this cauldron of competing interests and who are trying to do nothing more than survive from day to day. She comes in contact with those on both sides of the struggle, showing the impossibility of remaining unaffected by what is happening.

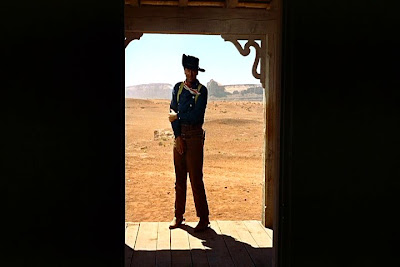

Zbigniew Cybulski emerged from this film a superstar. He would come to earn the nickname of the “Polish James Dean,” which I suppose is a result of the magnetism that both displayed on screen. But these are two very different actors. Whereas Dean’s roles constantly exuded unbridled passion, Cybulski plays Maciek in a very laidback and carefree manner. With the trademark glasses and constant smiles, it is amazing to think that the Maciek character is in the middle of carrying out a contract murder. Rather than being overwhelmed by the situation, he takes the time to pick up a woman and make jokes. The amazing thing is such antics do not come across as hyperbolic. Everything seems so natural.

In the end, though, I’ll disagree with assessments that overly shower Cybulski with praise and ignore the guiding force of the entire production. This is Wajda’s film. As the finale in a trilogy of films about Poland during and shortly after the war, Ashes and Diamonds remains Wajda’s greatest effort. The movie is undoubtedly stylish (it’s no coincidence that the subtitle of my DVD of the film reads “Essential Art House”). But such a chic style never sacrifices the gritty realism that Wajda is able to include in everything. He truly conveys the sense of a war-torn nation. And his shot composition in certain sequences is remarkable. The opening ambush scene and its memorable final shot in the church is an amazing way to start the film. And the sequence in which Maciek watches a pacing Szczuka in the hall of the hotel before stalking him to complete the contract is perfect. The fireworks bursting in the background as Szczuka stumbles toward him is brilliant stuff. He is also able to seamlessly integrate scenery and props directly into his shots, such as using the hanging crucifix or white sheets in the final chase scene. It’s obvious that the man was completely at home in controlling and directing the camera.

Rating: 9/10

Other Contenders for 1958: There are some huge films in 1958, and I have a feeling that many will choose one mentioned in this section. My second favorite film of this year, and the one that until recently was slated to be the pick as #1, is Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil. Aside from the head-scratching decision to cast Charlton Heston as a Mexican police officer, the rest of the film is amazing. It contains my favorite acting performance from Welles and aside from the awkward position producers put him in, Heston also delivers a fine performance. The other landmark movie of this year, and the one that I suspect will receive considerable support, is Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo. I really like it, even if I do place it behind other Hitchcock favorites like Rear Window, Psycho or Rebecca. Still, its status is undeniable and is widely accepted as Hitch’s greatest film.

The other films of 1958 that I love, but never really contended for the top spot: Man of the West (Anthony Mann), Mon Oncle (Jacques Tati), The Defiant Ones (Stanley Kramer), Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (Richard Brooks).